General Update / Contact Tracing: Intro / Digital Solutions / Privacy Concerns / Apps in the US

Today, I've decided to concentrate on contact tracing ... see if I can break this down into understandable chunks. It's been a while since we've heard about this on the news, but it's still a vital tool in the fight against epidemics of all kinds.

General Update

Overall, new cases are dropping. Active cases are still trying to go down (a good development). Deaths are still climbing at about the same rate, but should start going down sometime soon.

A lot of new cases seem to be associated with colleges and high schools opening up. For example, even though NC is roughly stable overall, the counties with schools are showing much higher activity.

Iowa, South Dakota, and North Dakota have blown up like crazy.

Everything else is about the same as usual.

Both presidential candidates in the last couple of weeks have presented comments on the coronavirus -- you can probably guess which candidate agrees with me, and which one is clueless. But neither one of them talked about contact tracing, and that concerns me a little.

Contact Tracing: Intro

So, what is it? Contact tracing has been around for centuries. The idea is that in order to stop a disease from spreading, you employ a little detective work to find out where the sickness came from and where it's going. Then you can figure out who to isolate and/or quarantine.

Hundreds of years ago, it was more difficult, but as technologies advanced, people could use tools to aid and speed up the effort, and save more lives. Imagine investigating an outbreak, figuring out the patterns and homing in on Patient Zero (remind you of any movie plots?).

At the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in the US, you probably heard some of the contact tracing results in the news, such as how the one nursing home in Washington infected several visitors who then took it to different cities. You may also remember that in these early stages, these people were quickly put into quarantine so that couldn't infect others.

Ultimately there came a time in late February when it became clear to everyone that the virus was loose and everywhere. It seemed that contact tracing stopped, but not really. It mainly happens in the background, but we still hear reports of "clusters" in the news. These are areas where it becomes clear that someone at some place infected many -- such as a nursing home, church, or parties.

And how do we know that these clusters are responsible and not a coincidental convergence of people who had already caught the virus from other places? It's because of the patterns. Whether you use Bayesian inference, Occam's Razor, or whatever you want to call it -- if you can see one group over here that's infected, and this adjacent group of people are not infected, it's very, very likely that the infection happened at the first gathering.

Or put in different words ... recently we've just had high schools open up. All of the kids start off healthy, but then within the first day, John's class has an outbreak of 10 kids, and Susie's class down the hall has none. Wouldn't it make sense to assume that someone in John's class infected the other 9, and that it happened in John's classroom? It would at least be the easiest explanation.

On the other hand, if every classroom showed infections in the first week evenly spread out, it's actually simpler to believe that the spread happened before the kids even came to school.

And guess which of the two patterns are being witnessed. If you answered that it's the chunky here and there outbreak pattern (rather than the everywhere pattern), then ... ding, ding, ding! You get a star.

That's contact tracing.

Contact Tracing: Digital Solutions

We Americans are actually pretty good at contact tracing, and practically anyone can be trained on how to do it. In fact, in response to the current pandemic, hundreds of thousands of people have been hired to do just that. And it really is amazing how we can find these patterns effectively.

But there's just one problem ... it's too slow. Very slow. By the time we figure out a cluster, it's too late. The virus has already spread and is likely starting the next set of clusters. Especially with asymptomatic spread, it becomes very difficult to beat and get in front of this virus. And that's why we currently have millions of people with active infections.

However, we have the technology to speed things up dramatically. In fact we could have already been done with the virus, and back to our normal fully open economy.

China and South Korea are extreme examples of countries who have used advanced technology to efficiently combat the virus.

Parts of China use a mandatory tracing app in conjunction with high-tech surveillance and Artificial Intelligence (face recognition) ... just like you may have seen in the TV Show "Person of Interest." When an infection is identified, the system goes through history of phone locations and video surveillance history to home-in on people most likely to be infected, and sends their phones a signal to trigger a red/yellow/green indication.

Green means "perfectly okay and able to do anything they want." Yellow means "intermediate risk of infection, and is restricted from certain activities." And red means "infection imminent, must stay in quarantine." And the result: they've gotten active cases down to practically zero, and new cases at a slow very manageable trickle.

South Korea has likewise incorporated their own surveillance and mobile phone system to battle COVID -- very similar to China, though not quite as invasive. They've done an excellent job keeping the virus at bay, all while avoiding a total lockdown (though they have shut down individual businesses when infected as well as hotspots like bars in some locations).

But get this -- after their initial first wave and after they began instituting their system, South Korea has had two further noticeable outbreaks, and they both involved a collection of people who had circumvented the contact tracing setup, allowing the virus to spread. The first outbreak (a little one) involved LGBT concerns, starting with gay bars, which then inspired infected people not to cooperate, being unwilling to out their LGBT friends. It took about a month or so to bring cases back down. The second outbreak (much bigger) involved a big church in Seoul, caused by a desire to stop safety precautions and let people have the freedom to do whatever they want (sound familiar?). I'll write about this in more detail next week. It'll likely take at least another month if not two to bring these cases back down again, but I have faith ... as Korea is demonstrating that the technology-aided contact tracing works ...

... as long as the people cooperate.

Contact Tracing: Privacy Concerns

Up to now, if you're a red-blooded American like me, you're probably saying, "This would never work in the USA," and you're probably right. In fact, at the end of that video on China I shared above, it talks about how part of the code is sending location and timing information to the police, though not being disclosed to the participants.

So, yes, it's scary. I think this is why both the Republicans and Democrats shy away from this type of technology. There's no way we could institute anything that would violate our privacy and jeopardize our rights and freedoms.

If only there were a non-invasive technology solution -- some kind of compromise. But wait ... there is!

Google and Apple have worked together to produce such technology -- the backbone of an app -- and it's already installed on all Google/Apple phones with Bluetooth that has upgraded in the last couple of months. (Don't worry -- it's useless without an app to activate it.)

Before you get scared off, you need to understand how it works. And you'll have to believe me when I say that in terms of privacy, this technology is much more secure and privacy-protecting than practically every single app you're already using on your phone.

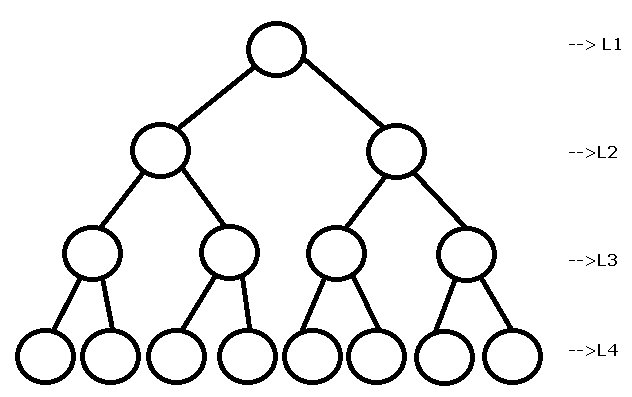

I found this cute graphic that explains the idea in simple terms ...

Just in case this picture expires, I'll repeat it here in my own words. Each phone creates its own random string, and nobody knows who this string belongs to -- not even the central database.

As you walk around, your phone's Bluetooth will talk to other phones and swap random strings, and stores the information for 14 days. So after a couple of weeks, your phone has a collection of everything your phone has broadcasted, and a collection of random strings received from other phone, and also possibly how close you were and how long the encounter was.

If you catch COVID-19, your phone sends the 14 days worth of "sent" strings to the central database. Keep in mind that nobody knows who sent which messages, and absolutely nothing can be traced to anybody. But how do the other people find out that you got COVID-19?

Simple ... their phones will check the central database -- if any of their "received" messages matches what's in the database, they will get a message: "You have been exposed to the virus for 10 minutes -- you should get tested" -- or perhaps some other message: "You need to self-quarantine for five days."

But in no case can the sent or received messages be hacked to reveal its sender ... it's mathematically impossible. This is similar to the double lock and key encryption methods used to secure communications daily. That works like this: Sender A puts a lock on his message and sends it to Receiver B. Then Receiver B puts a lock on the message and sends it back to Sender A. Now there are two locks on the message. Then Sender A can unlock his own lock, send it back to Receiver B. And finally Receiver B can unlock his own lock and read the message. No one else can intercept this message because either Sender A's lock or Receiver B's lock will be on the message.

Of course, there exist higher-level hacks or indirect hacks that can take advantage of any secure setup. For example, Criminal C in the message scenario above can pretend to be Receiver B and use his own key to get the message instead of Receiver B. This happened to me once when I went to a bad Yahoo News page and typed in my credentials to join a discussion -- my email account had been hacked.

And there are ways to trick a COVID app -- such as broadcasting a false positive report just to be malicious (though we could lock that down by requiring a doctor's key to send a positive report). Also, human contact tracers might be able to find out where you've been if a whole bunch of other people from that same place test positive at the same time -- not through the app, but through good old fashioned detective work.

Despite these high-level hacks, people still can't get any of your personal information -- it is safe in that respect. Compare that to the apps you love to use today, but then you get bombarded by ads about those items you Googled yesterday. Now, those are apps that know who you are.

Here is an official announcement from Google/Apple explaining in their own words how their Exposure Notifications System works (repeating a lot of what was said above):

Lastly, I must point out that no COVID app can run effectively without the backing of the government. Everyone has to use it. If everyone is using different apps, it just wouldn't work, as App A can't see App B. Several countries in Europe either use the Google/Apple technology or something similar to it, and countries using the same technology may be compatible with other countries. See this article for more details:

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-europe-tech/europe-pins-hopes-on-smarter-coronavirus-contact-tracing-apps-idUSKBN23B1OA

Contact Tracing: Apps in the US

In the US, alas, there is no national tracing app, so that framework sitting on your phone right now is doing absolutely nothing -- just sitting there. Each individual state is handling contact tracing in different ways. Starting in August 2020, some states have started using the Google/Apple technology. Virginia was the first with Covidwise. And then North Dakota moved from their privacy invasive solution (Care19 Diary) to the Google solution (Care19 Alert). And supposedly, 20 states are in the works to launch their own versions soon.

Other states are using home-grown apps, which are usually on the invasive side, storing location information (and in the case of North Dakota actually selling the information to 3rd parties), and they really aren't that good. Some involve filling out questionnaires, but no real tracking.

And some apps actually mimic Google/Apple.

Here's another article on states using the Google/Apple solution ... I strongly recommend reading it and watching its embedded video to get more information.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/08/17/coronavirus-exposure-notification-app/

In my opinion, the Google/Apple based apps are the safest to use in terms of privacy. Some of the other apps (not Google/Apple) being used throughout the states may have other invasive features added, such as sending GPS location or phone numbers. If at all possible -- you want to stay away from those apps because they really are invading your privacy when a much safer alternative exists.

Here's a quick list of public apps I could find in the US:

- Alabama: GuideSafe (Google/Apple)

- Alaska: COVID Secure (sounds invasive -- you can receive notifications of positive test results from friends and employees, and location collection unknown -- claims information is "safe" on their servers -- sounds mandatory in some cases)

- Arizona: Covid Watch (Google/Apple) -- limited locations -- only college campuses?

- Florida: CombatCOVID -- sounds similar to Google/Apple, and they claim not to use or collect location information, but I'm having a hard time finding out for sure. And right now it's only being used in the southern counties.

- Nevada: COVID Trace (Google/Apple)

- North Dakota: Care19 Alert (Google/Apple) and optional Care19 Diary (location -- don't use it)

- Pennsylvania: Coming Soon (Google/Apple)

- South Carolina: Coming Soon (Google/Apple)

- South Dakota: Care19 Diary App (location -- don't use it)

- Utah: Healthy Together (location -- don't use it -- hardly anyone uses it)

- Virginia: Covidwise (Google/Apple)

- Wyoming: Care19 Alert (Google/Apple) and optional Care19 Diary (location -- don't use it)

This alternative app also looks interesting, but I'm not sure where it's being used other than college campuses: NOVID. Instead of using Bluetooth, it uses the microphone to pick up high-frequency signals from other phones using the same app.

Will these apps work? This is still up in the air, though Europe seems to be doing well with them (until a country stops using them). We'll see if they continue to catch on.

So, keep an eye out ... if you see an app in your location that protects your information as I described above, then go ahead and turn it on, and help us defeat the virus. It would really help us to more fully open up our economy without giving much up in return -- it seems to me to be a no-brainer.

If you have any questions, or would like for me to explain any aspect of these apps, just let me know.

Keep well, and stay safe!